The Kent State massacre, 45 years later, remains a red mark on our nation’s history. On a sunny spring day, May 4th, 1970, National Guardsmen attacked—with a 13 second barrage of bullets—a group of unarmed students, gathered for an anti-war protest. Nine were wounded, and four (Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandy Scheuer and William Schroeder) were killed. Those four, forever immortalized in Neil Young’s “Ohio,” bear witness to a divisive political landscape that exists as much today as it existed in 1970. The recent events in Ferguson and Baltimore make the remembrance of this national tragedy all the more timely.

Alan Canfora, a young student at Kent State, and a member of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), was involved in the Kent protests during the days leading up to the massacre. These protests, sparked by Nixon’s announcement that the Vietnam War was to be expanded into Cambodia, came at a particularly emotional time for Canfora. A few days earlier, he had attended the funeral of his friend, Bill Caldwell, who was killed in Vietnam. As a memorial, Canfora prepared a black flag for the May 4th demonstration, declaring “I purposefully chose black material to match my dark mood of despair and anger following the recent death of my friend.”

A photograph of Canfora waving the black flag before a crouched, aiming regiment, moments before they fired 67 rounds into a group of unarmed demonstrators and bystanders, has become one of the iconic images of that tragic event and of the anti-war movement itself.

Alan Canfora, on the practice football field, 250 feet away from aiming Guardsmen. Ten minutes before the massacre. Photo by John Filo.

Minutes after that photo was snapped, the National Guard fired a volley into the crowd. Canfora, who was shot through the wrist by an M-1 bullet, claims that only eight of the thirteen victims were active in the protest. Five were simply bystanders, including Sandra Scheuer and William Schroeder who were killed while walking to class.

Canfora’s website contains a heart-breaking account of the events of May 4th. What is noteworthy, throughout Canfora’s recollection, is the utter disbelief that the Guard would be using “real” bullets on unarmed students:Just as I reached safety, kneeling behind that beautiful tree during the first seconds of gunfire, I felt a sharp pain in my right wrist when an M-1 bullet passed through my arm. With shock and utter disbelief, I immediately thought to myself: “I’ve been shot! It seems like a nightmare but this is real. I’ve really been shot!” My pain was great during that unique moment of unprecedented anguish but I had another serious concern: the bullets were continuing to rain in my direction for another 11 or 12 seconds.

Among the 76 Ohio National Guard soldiers stretched across the hilltop, only about a dozen members of Troop G—the death squad—stood calmly aiming in a firing line. They killed four Kent State University students and wounded nine others, including me. One wounded victim, Dean Kahler, remains paralyzed as a result.

During the gunfire, I was in great pain and distress but quite aware that I had to remain tucked behind that narrow, young tree which absorbed several bullets intended for me.

I then heard my roommate Tom Grace screaming his severe pain after a bullet passed through his left ankle. While the bullets were still flying, I yelled over to my best friend, Tom Grace, “Stay down! Stay down! It’s only buckshot!”

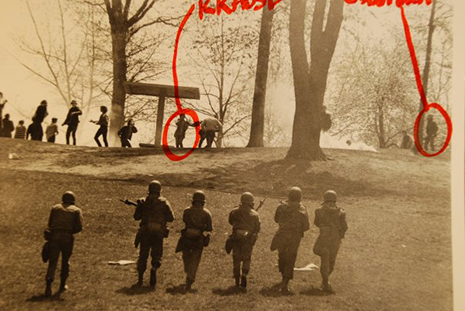

Canfora, wounded, kneeling behind a tree, an M-1 bullet wound having pierced his right wrist—225 feet downhill from Ohio National Guard shooters. This tree saved Canfora as well as Tom “Aquinas” Miller, who was standing behind the tree. Canfora and Miller are looking right to Tom Grace who was shot through his left foot nearby.

Even as he had reached the hospital for treatment of his wound:When I got to the hospital, as I walked alone toward the emergency room door, I looked inside the open rear door of a parked ambulance. I saw my friend Jeff Miller lying dead and bloody on a stretcher. I assumed he was only unconscious from a facial flesh wound. I still wrongly-assumed non-lethal shotguns shot us.

During those terrible seconds as I stood alone gazing at my friend’s bloody form, I vainly hoped that plastic surgery would repair Jeff’s face where a gaping 2-inch bloody hole destroyed Jeff’s always-smiling face. I did not know that a powerful M-1 bullet had passed through Jeff’s head and he was killed instantly.

Photo by John Filo

Canfora went on to graduate Kent State with a Bachelor’s Degree in General Studies and a Master’s Degree in Library Science, and has remained a vociferous activist, both as a student organizer, and in the justice movement for the victims of May 4. He took time out of his busy schedule, working on the 45th anniversary commemoration, to talk to Dangerous Minds about the events at Kent State and their repercussions today.

The iconic photograph of you waving the black flag before a National Guard regiment, with weapons raised and pointed at you, has been compared to the image of the so-called “tank man” at Tiananmen Square. Both photographs evoke a David vs Goliath sentiment—standing up to a monstrously armed force of authority. Of course, our cultural narrative programming has us shocked that an unarmed student would be fired upon in the United States—and maybe also shocked that a man standing in front of a tank in Communist China could stop that tank from rolling forward. Do you see similarities in the two images?

Alan Canfora: The “tank man” definitely was risking his life, at a time when many students were actually killed. By standing in front of the tank he showed great courage. It’s similar to my situation in 1970 in that he did risk his life for the cause that he believed in.

So, when that image was taken, at that moment you felt that your life was in danger?

AC: Absolutely. I think any time that there’s someone aiming guns at you with their fingers on the triggers, you definitely think that your life may be in danger. I had to confront the possibility at that moment. I certainly didn’t plan for the moment. I had no idea I would be in that situation until the Guardsmen got down and started aiming at me. It seemed like an absurd situation—I didn’t think that I was doing anything to deserve being shot or to even have guns aimed at me—I was 150 feet away—it was broad daylight—they hadn’t shot anyone while the National Guard was on campus the two previous evenings, even though some students were stabbed by bayonets, and other students were beaten with clubs the night before on May 3rd. I just didn’t think that in broad daylight on a sunny Spring afternoon that they would just start shooting into a crowd of unarmed students.

At that moment I started thinking about why I was there. Only ten days prior, myself and my roommates had attended the funeral of a nineteen-year-old soldier who was killed in Vietnam—his name was Bill Caldwell—so we were at that funeral on April 24th, and we were already very anti-war, and some of us were very experienced with protest actions… and at that funeral we swore a vow that we would take action at the soonest opportunity to send our message to President Nixon that he should stop the war in Vietnam. Too many young people were coming home dead or wounded, and we understood that the war in Vietnam was genocidal—our government was killing two or three million Asians.

Six days after that funeral, Cambodia was invaded by Nixon—the war was expanded into another country. We watched the announcement on television, and we were very angry, and we said tomorrow night we are going into action. From May 1st through 4th, we were some of the leading militants on the streets of Kent. And so when I was out there with them aiming the guns at me, that was the culmination of four days of protests—and I didn’t anticipate that moment, but I had to think to myself “this is why we’re out here—to make the most powerful statement that we can about stopping the war.” So I didn’t back down, I stood my ground there, and I basically tried to communicate with the Guardsmen who were aiming at me from 150 feet away… I remember shouting at them “if you support the war in Vietnam, then why aren’t you IN Vietnam?” I said “my friend was killed there just a few days ago, and we attended his funeral, and that’s why we’re out here—we’re trying to stop the war.”

Their commanding officer ordered them to stand up and then march away—it looked like a retreat—they started going back up this hill, and then when they got to the hilltop, that’s when they got the order to turn and fire.

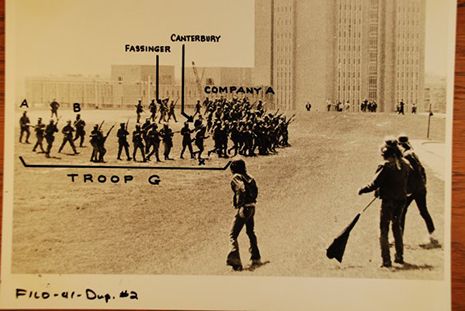

The Guardsmen depart the practice field in what many thought was a retreat. They soon marched uphill & fired 67 gunshots downhill into a crowd of unarmed students. Canfora was shot when he ran to a tree—225 feet away from the hilltop shooters.

That’s what seems so absurd—there was no imminent threat to them whatsoever.

AC: They were under no significant threat throughout the entire twenty-four minute confrontation—we all knew that they had stabbed people the night before—every step of the [confrontation] is on film and you can see second-by-second that every time they marched toward the students, the students evacuated.

Just as they started to shoot, there was one student standing off to the side raising his middle finger toward the Guard—he was shot twice—once in the stomach, once in the ankle. He was 72 feet away. Another student behind him was 90 feet away, just taking pictures—he got shot in his chest. Down near the bottom of the hill is where I was—225 feet away when I got shot through my right wrist. When I heard the guns firing I thought “they must be firing blanks, there’s no reason to shoot.” But I thought “just in case these are real bullets,” I started to zig and zag as the bullets were flying around me and I jumped behind a tree, and just as I did I felt a bullet go through my right wrist.

Having read your heart-breaking account of those events, what affected me the most was the confusion you felt. The assumption that the Guardsmen would not have bullets in their guns—and then, even when you were aware that you had been shot, you were still assuming that it must have been “buck shot”—I get the sense that the realizations about the use of deadly force in that moment may have been just as traumatic for you as the physical pain of being wounded.

AC: It just didn’t seem like any kind of a shooting situation, in fact, when you consider what had happened already on May 1st in downtown Kent—about 43 windows were smashed out—about 28 of those were in one bank, and other specific corporate targets were hit like the gas company, the electric company, the telephone company, the conservative Republican newspaper—those windows were all smashed out and nobody got shot down there that night—fourteen students were arrested. The next night, the Kent State ROTC building was burned down—the National Guard arrived that evening and they didn’t shoot anybody—so, by May 3rd several students were bayoneted after a peaceful sit-in in the street. Several male and female students were slashed and stabbed by the National Guard, and a bunch of students were beaten with clubs—but no one was shot. [By comparison] the rally on May 4th was anti-climactic. We didn’t have any plan or agenda—it was just a gathering. As soon as one student got up and spoke about a national student’s strike, that’s when the Guardsmen attacked with teargas and then [shortly thereafter] began aiming guns at me and others. To attack our rally on May 4th—we were doing NOTHING wrong—we were just standing there starting to chant anti-war slogans. One kid just started to speak, and that’s when they attacked. Ultimately they shot 67 gunshots into a crowd of unarmed students—and that was the ultimate absurdity.

Canfora, upper right in photo, face covered by scarf, with black flag at hilltop as Ohio National Guard attack and chase students away from Victory Bell and over Blanket Hill. Note KSU student, Allison Krause, under concrete “pagoda” at hilltop. Allison was shot in the chest & killed 20 minutes later.

There’s no logic to it.

AC: It’s so illogical unless you understand that among the 26 Guardsmen who marched out against us, tear-gassing us, chasing us over a hill, there was a small group there called Troop G of the 107th cavalry unit, there were about a dozen of them and several of their officers—they were like the cream of the crop of the hardcore nastiest National Guardsmen on the scene. When those guys knelt and started aiming, those guys were picking out their targets, and who they were aiming at?—there were two black flags that day, I made both of them, and my room-mate was carrying the other one—who’s carrying a black flag? Who’s throwing stones? Who’s giving the finger? Who’s cursing at them? Who’s taunting them? And among the group that they ended up shooting, Jeff Miller was very active—he was killed. Allison Krauss threw a couple of stones—she was killed. I was waving a black flag—I got shot. Joe Louis was giving the finger—he got shot. John Grace was a protester standing next to me when he got shot through his foot. Eight of the thirteen victims were active in the protest. Five were just by-standers.

You had a group of Guardsmen who were on a twenty-four minute hunting expedition, seeking human prey. And once they committed that massacre, they simply turned, regrouped, and marched away. Mission accomplished.

And what did the Guard do after the shooting?

AC: They had three big lies that they tried to perpetrate. The general had two news conferences that afternoon and said, first of all, “the students were shooting at us, there was a sniper, and we returned gunfire.” That was a lie. The second big lie was “the students were about five feet from us, about to overrun us, we thought our lives were in danger, and we thought they were gonna take our guns from us.” Well, the photographs came out the next day, and the closest student was not five feet away, but 72 feet away. The third big lie was they said the students were throwing rocks, bottles, and other objects, and their lives were in danger so they fired in self-defense. That was proven to be false. When the FBI came to town over the next two months, at the end of their investigation, the Department of Justice concluded that the National Guard’s claim of self-defense was, and I quote, “fabricated, subsequent to the events.”

Some people were throwing stones, some people felt so provoked that they picked up whatever was lying on the ground—but there was such a distance between the students and Guardsmen that day, that the stones fell short—there were also photographs showing Guardsmen throwing stones at students—and those fell short too. So both sides stopped that—it was basically a stalemate. And then when the [Guardsmen] were retreating, we felt “the confrontation is over, they’re going away.” And they got to the top of the hill and that’s when there was a verbal command, “Right here. Point. FIRE.”

A student cassette recording made at the scene was found which corroborates this—verified so far by three digital audio analysts.

All of this information and evidence is on my website alancanfora.com and on may4.org.

>This was an intentional massacre based on an order to fire.

Canfora returns a tear-gas cannister toward the attacking Guardsmen.

Discussion of the events at Kent State seems especially timely considering many of the events that have recently occurred in Ferguson and Baltimore. We have seen the National Guard called out, and it seems to have the opposite of the intended effect, making people much more frustrated, angry, and volatile.

AC: I think it does. For example, when we saw those 1200 Guards rolling into Kent on May 2nd, we thought it was provocative to send in armed troops against students who were only assaulting property. And we knew that same thing was happening all across the country. It was like throwing fuel onto the fire. Especially with those “weekend warriors,” as they were known. These were not full-time, professional, law enforcement personnel. They were beating the students, and stabbing the students, and ultimately they shot us. They were poorly trained, they were over-armed, and they had very poor leadership—unlike full-time professional law enforcement personnel. It’s really a recipe for disaster.

I don’t think the National Guard should be called into a civic disturbance. No longer are National Guardsmen sent into a crowd control situation armed with M-1 rifles. Now days they try to emphasize non-lethal weapons, which of course are still actually lethal. But I don’t think you’ll see another situation where they shoot 67 gunshots into a crowd of unarmed protesters. That was such an extreme example of excessive force. It was about a year after Kent State that they started using rubber bullets, plastic pellets, beanbags, and different things like that. I don’t think you’ll see the same kind of carnage on a mass scale—at least I hope not. When you consider the volatility of our country right now, when you have people that are so oppressed because of income inequality and class discrimination—people that are driven further and further down into poverty, that they are so desperate that they go into the streets—I think there’s a danger that this could be happening not just in Baltimore or in Ferguson, but it could start happening across the country simultaneously [and if this occurred] people would realize that our country had descended into a revolutionary situation.

There’s a cultural polarization that takes place that allows for events such as these, and then people are actually surprised when it happens!

AC: Our governor at the time, James Rhodes, was very hostile against civil rights protests in the urban areas, but he was also very hostile to student protests - especially the ones right before the upcoming election - he was already the governor of Ohio but he was seeking to become a US senator - and he was 8% behind in the public opinion polls [due to student protests]. So he was desperate, and he had to act like he was cracking down on the protesters. He came to Kent and gave a news conference on May 3rd, the day before the massacre, and was pounding his fist on the podium with all of the TV cameras pointed at him, and he said “these Kent State students are the worst type of people we harbor in America. They’re worse than the Communists and the Brownshirts.” And he pounded his fists and said “we’re going to eradicate the problem.” He exaggerated the situation in order to appeal to the conservative Republican voters that were going to be voting in that primary election on May 5th. And he basically provoked or incited the National Guard to commit violence that evening when they stabbed students, and also the next day when they shot us.

April 7, 1970, less than a month before the Kent State shootings, Governor Ronald Reagan in California said “these students want disruption - if it takes a bloodbath, let’s get it over with.”

There is a real danger when a situation is polarized—and then you put guns into the hands of the people that are the most hateful, and that’s a formula for a disaster. They hated us, they didn’t understand us, they resented us, to the point where they shot us with absolutely no hesitation.

Canfora and roommate confront Ohio National Guard from 250-feet distance on practice football field minutes before Guardsmen march uphill & shoot.

Anyone who experiences a traumatic situation like this deals with effects of it for the rest of their lives. Many members of the radical left or anti-war movement of the Vietnam era have assimilated into mainstream culture. Would you say that being shot in 1970 was a crystallizing moment that kept you dedicated to activism?

AC: No. My father was a union activist in Akron, Ohio, with the UAW; and he was very political, and raised all four of his kids to be very strongly liberal and progressive minded. He led a two month strike against Goodyear in the 1950s. In the ‘60s he was on our hometown City Council as a liberal Democrat—a very progressive guy. So we were already politicized in my family from the time, even back to the 1950s when my dad opposed a “right to work” law—he had us aware of that stuff even when I was nine years old. When I saw the students beaten in the streets at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, I knew that I wanted to become an activist—to try to fight for the same cause. At Kent State, I first joined the College Democrats, and within a month I quit them and joined the SDS, because they were more leftist intellectuals - the leadership of the SDS at Kent was among the most brilliant and militant in the whole country.

Jerry Casale from DEVO[was in the Kent State SDS, and] was there, and he witnessed the massacre. Two of his good friends, Jeff Miller and Allison Krauss were killed, and that radicalized a whole lot of people who witnessed the event including Jerry Casale who was already a radical. He formulated his theory of de-evolution—that human society was de-evolving, and the Kent State massacre helped him reach that conclusion—that society was not evolving any longer.

Terry Robbins [of the Weathermen], who got blown up in a townhouse, saw me at the SDS events and looked at me and said “you’re an action freak.” For Terry Robbins to call me an “action freak”... I consider that to be quite a compliment.

By 1969 most of the leadership of SDS had gone underground and joined the Weathermen. I did not. I thought that was a tactical mistake. I thought we had to stay above ground and continue to organize and fight against the war, out in the open. There were only a few of us from SDS still there, and we continued to remain anti-war, and when the invasion of Cambodia happened in the Spring of ‘70 we were among the most active students, sparking the protests. I don’t think that being shot made me more of an activist, but it made me more of a proponent for justice against the cover-up of murder.

“They hated us, they didn’t understand us, they resented us, to the point where they shot us with absolutely no hesitation.”

In finishing up our conversation, I mentioned, off-the-cuff, that many people consider Canfora to be an American hero. He was very quick to dismiss such praise, stating, “I’ve never considered myself to be a hero - I consider myself a foot soldier in the anti-war army.”

Canfora will be participating in the 45th annual commemoration at Kent State and is currently in final-edit of his memoir, which should be wrapped up by Summer. His website contains volumes of information on the events at Kent State, and is well worth your time and research.

Tuesday, May 5, 2015

On the 45th anniversary of the Kent State massacre, a talk with one of the students who got shot

from Dangerous Minds:

Labels:

activism,

civil disobedience,

government,

history,

kent state,

militarization,

Politics,

riots,

student protests

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment