In our race to embrace new technologies much has been lost. During the 50s and 60s General Electric spokesman Ronald Reagan appeared regularly on American television declaring with godlike certainty “that progress is our most important product.” And we bought it. And we’re buying it still.

Until their recent resurgence, vinyl records were a thing of the past. Now it’s compact discs that are being phased out. DVDs and Blu-rays are next. The powers that be want us streaming data through the ether without the hassle or production costs of actually making something you can hold in your hand and own, not just store in a cloud somewhere. In our embrace of the new, faster, most convenient thing, we’ve lost a substantial amount of what we love about the things we love, the things that make our lives more beautiful. My Sonos streaming device is an ugly block of white plastic. My turntable, a Thorens with a beautiful wooden plinth, is a masterpiece of design and function, gorgeous to look at, soulful, unique. My record collection is not just, to my ears, a superior way to listen to music, it is a wonderland of marvelous sleeve art, label design and picture discs. All of which I can hold in my hands, all responding to gravity and easily handed off to a friend to appreciate as much as I do. No one ever comes into my home and asks to see my set lists on Deezer or flips through my Amazon cloud collection.

The phasing out of vinyl, CD, DVD, celluloid, happened so fast that a lot of people were caught by surprise. I own a vintage audio store and people are coming in on a regular basis to buy CD players because the local big box stores don’t sell them anymore. You might be able to find a shitty player that will shuffle dozens of CDs or some crappy all-in-one system. But a good single tray player with a decent digital audio chip is getting harder to find unless you move into expensive audiophile gear territory. If you told me even five years ago that CD players and CDs themselves would become collectible I would have laughed and said you were nuts. Guess what? Anyone want to buy a Suicide Commandos’ CD for $400. I got one.

The return of vinyl is wonderful for many of us. But the big three music corporations hate it. They’ve had to shift back to making stuff. And they have to pay a lot of people to make it. The new records sold in my store put scores of people to work, from the guys who make my record bins, to workers pressing the vinyl to the artists designing record jackets again. Add to that the truckers who move the vinyl, the folks in my store who sell it and homegrown turntable manufacturers like U-Turn who can’t keep up with production demands. All those people making livings thanks to vinyl. Not to mention, the musicians who now have more control over their product and profit when they produce their own records. Yes, a record costs much more than a CD to make or an MP3 to stream. But a record is something special to a bands’ fans. It is an artifact, a totem, something you hold close to your heart knowing that not everyone owns one of these slabs of black magic. With demand so high and current production so limited, every record made today is almost instantly collectible. You may be fine listening to iTunes or Amazon cloud, but vinyl is something you want to own. It is precious. It is art.

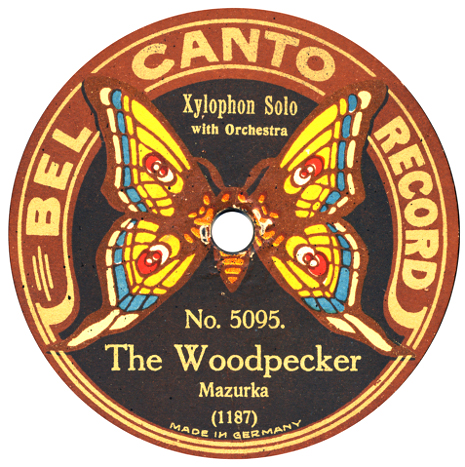

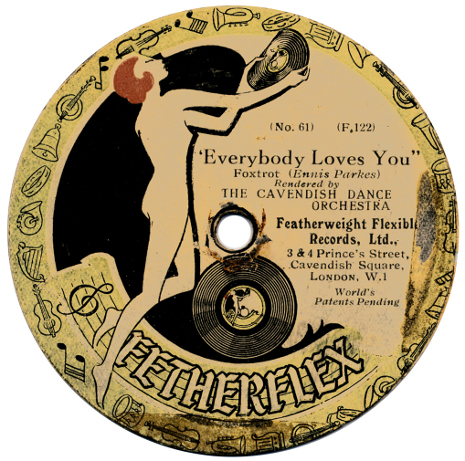

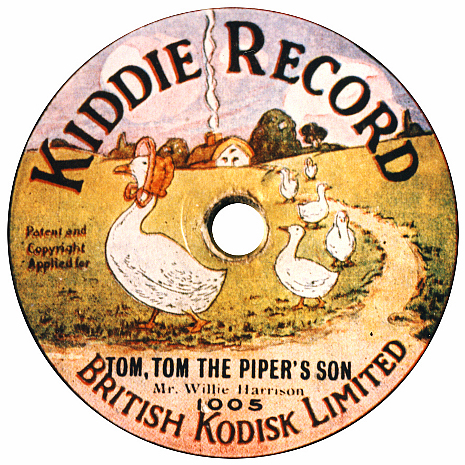

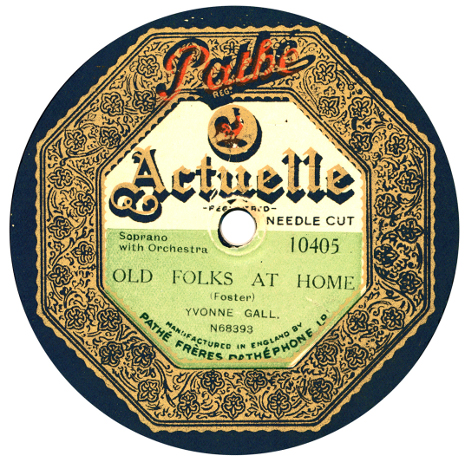

So that’s my vinyl rant. It was all leading up to sharing these beautiful 78rpm record labels produced in Britain between the years of 1898 and 1926. Enjoy them. And be happy that we may be seeing their like again, if not already.

More of these lovely labels can be viewed at Early 78s UK.

It's in my eyes, and it doesn't look that way to me, In my eyes. - Minor Threat

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Technology's lost art: The ancient magic of the record label

from Dangerous Minds:

No comments:

Post a Comment