Before the completion of his political radicalization, the great Nigerian creator of Afrobeat music Fela Kuti was a purveyor of another acutely African music called Highlife. Highlife was, at the time, a dance music that married African percussion and Western-style horn and guitar sections, creating a specifically Nigerian/Ghanan jazz sound. Around the 1930s, the style spread through the continent, and a modernized version remains popular today. From The Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora:

In 1930, Sibo, a Kru man, established a brass band in Ghana that played both African and European music; in Nigeria about the same time, the Calabar Brass Band moved to Lagos. Bothe events established the roots of highlife music in the two countries. Generally, as the music and its accompanying highlife dance spread across West Africa, each region maintained its ethnic specificity by composing songs in the local language, and some bands, especially the multinational ones, created compositions in English or pidgin English. Typical highlife songs covered topics ranging from love to social, philosophical, and the occasional political commentary.

Several factors contributed to the decline of highlife music. One major factor was the wave of independence sweeping through colonial Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. As countries attained independence, they lost vital connections they once shared through the British colonial system. Each new nation turned inward, focusing on developing independently. Closely related to this were the political unrest in Ghana and Nigeria. The 1965 coup d’etat that swept President Nkrumah from power also stifled his favored projects, including the state patronage of highlife music. The Nigerian Civil War (1969-1971) had an even more devastating impact because many of its prominent musicians were located in Biafra where the war raged the most. Finally, there was the widely, internationally popular soul music with its strong appeal to the younger generation, and West African youths proved to be no exception. Suddenly, highlife was no longer hip; it slipped into the memory lane of the middle-aged.

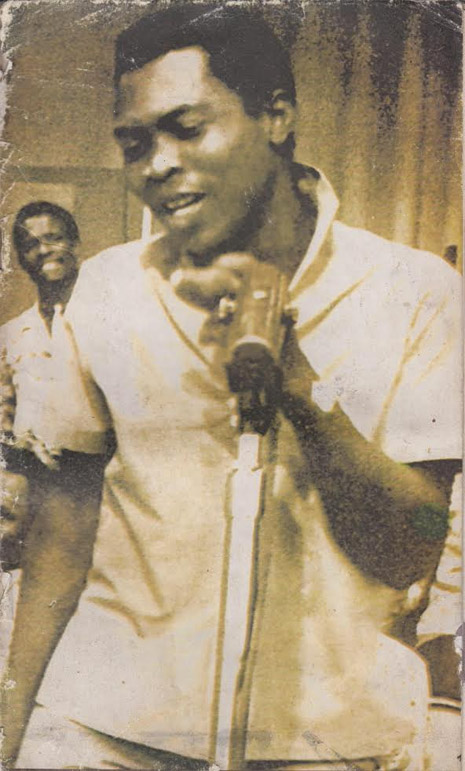

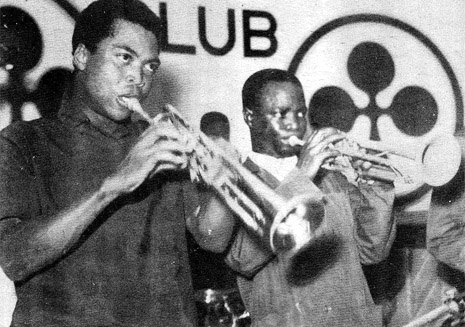

Photos circa 1966, give or take.

During the 1960s, after returning to Nigeria from his formal music studies in London, Fela led a Highlife band called Koola Lobitos. The band, like the music itself, was a mix of Africans and Westerners, and Kuti experienced success in the form. He was plentifully recorded, but little of that documentation made it to the west (an insanely thorough discography of those years can be seen at this link, revealing a massive trove of tantalizingly rare Fela records). The best record we’ve had of those years was The ‘69 Los Angeles Sessions. The tracks were recorded, like it says on the box, in 1969, in Los Angeles, under time duress as the band had been reported to the INS as being in the country without work permits!

But entirely legal or not, it was during his US visits that Kuti encountered the Black Power movement and books like Black Man of the Nile, which sped his already growing politicization, transforming him into the active revolutionary, wildly innovative and prolific musician, and controversial figure (he was also a prolific polygamist) who became famous in the ‘70s for the captivating, hypnotic chimera of Highlife, funk and free jazz he called Afrobeat.

Kuti’s Afrobeat phase was long and amply documented, lasting the rest of Kuti’s life (he passed in 1997 of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma)—in fact, all of his Western releases are legitimately streaming for free, if you’ve got any curiosity to sate—but new compilation from Knitting Factory of his Koola Lobitos years aims to fill in the gaps in Westerners’ knowledge of his early years. Highlife-Jazz and Afro-Soul (1963-1969) was released last week, and while the collection contains some overlap with the 1969 sessions release, plenty of it has been mostly unheard in the West. Check out the genre anthem “It’s Highlife Time” and the almost Stax-y “I Know Your Feeling.”

Given that we’re talking about Fela and this weekend is (ugh) Record Store Day, we’d be remiss if we neglected to mention one of this year’s pitifully few genuinely interesting RSD releases—a 10” single of “I Go Shout Plenty” b/w “Frustration.” The songs were recorded in 1976, for an intended 1977 release, but the Nigerian government’s infamous and shocking attack on Kuti’s communal home, during which his mother was killed by defenestration, waylaid that and other Kuti releases. Both songs eventually made their way onto releases in the 1980s.

No comments:

Post a Comment